Here's the only rule that applies to pedestrian behavior: people take the shortest path possible. It's that simple. Yes, we factor in terrain, safety, how late we are, traffic, etc., but all of that falls under "possible", and the fact is that human are willing to push their limits in all of those considerations when it comes to taking the very shortest path. There's a whole other anthropological discussion on why this is true, but for urban planners, we just have to understand how people are wired, now why we're wired that way (though it's pretty clear that a lot of survival advantages would come from a "shortest path" wiring in our brains).

The urban planning lesson is to always assume that people will take the shortest route, and plan for it. Sometimes, that's a chalenge when environmental or safety concerns exist, but may not be perceived or understood by pedestrians -- these are the cases where a lot of design goes into making that shortest path a safe one. Major street crossings are a great example, and today we're really paying the price for not understanding this principle in suburban road design, where engineers in years past attempted to force pedestrians out of direction in order to minimize the number of crosswalks on major streets. This has resulted in our major streets being far more dangerous than freeways when it comes to fatal and injury accidents, and we're now only beginning to retrofit the system to make the shortest path a safe one. Lots more to do on that front, unfortunately.

How does this apply to trails? One obvious way is when trail designs loop around in a less-than-obvious way that isn't dictated by terrain, safety or scenery. Our brains tells us that we're meandering for no reason, it the trail becomes frustrating -- but if the meander takes us around a wetland, to a viewpoint or establishes a clearly better grade, then our brains accept it as the most efficient route. In this way, boot paths tell us where the meanders are too far out of direction for hikers. In some cases (switchbacks), it may be true that enough hikers understand the benefits of the out-of-direction design to enforce trail-cutting through signs or education. But when there's a destination (a viewpoint, lakeshore, waterfall), good luck keeping people out, once the boot path is formed.

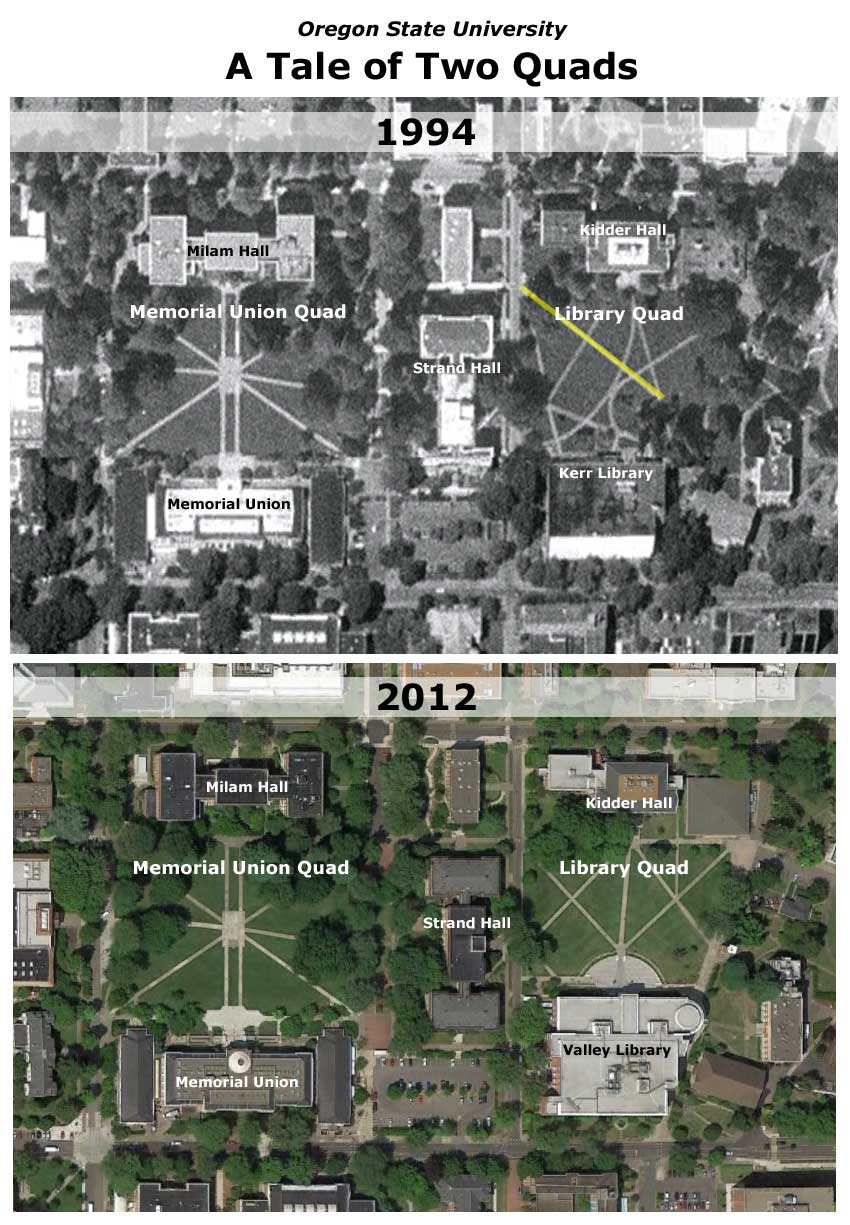

This is where the case study I use from Oregon State University illustrates the point, perfectly. On the air photos below, you can see the two large quads that front the Memorial Union and Valley Library, respectively. When the Kerr Library was built, the sidewalks in the quad design reflected "modern" 1960s thinking that went along with curvy suburban street systems. In no time, students voted with their feet, and organically created a shortest-path addition to the network that mimicked the much more efficient, traditional Memorial Union Quad - a diagonal route across the entire quad where no reasonable alternative existed. I've highlighted this boot path in yellow. It was eventually paved in the 1980s, as students refused to stay off -- even if it meant walking in slippery mud and walking past "keep off the grass" signs. This is the power of the "shortest path" wiring in our brain.

When the Kerr Library was greatly expanded to become the Valley Library in 1999, it triggered a redo of the Library Quad, and voila! Architects had returned to their traditional roots, and understood the shortest path principle, once again. The new design covers all direct routes efficiently, and even reduced the amount of paving in the process. No surprise that it looks a lot like the Memorial Union Quad design, as these traditional principles are pretty timeless.

In the urban context, I encourage young planners to look around for signs of where people are already walking, and put themselves in the mind of the pedestrian in figuring out how to make an informal path both safe and sustainable. This is no different than trail planning -- and you can see where I'm coming from when I generally advocate to formalize trails that are already well established, albeit in a safe and sustainable way. I also see this basic tenet violated frequently in new trail designs, though I do think we're trending back in the right (and direct!) direction.

Okay, enough geeking out this morning...

Tom